Introduction

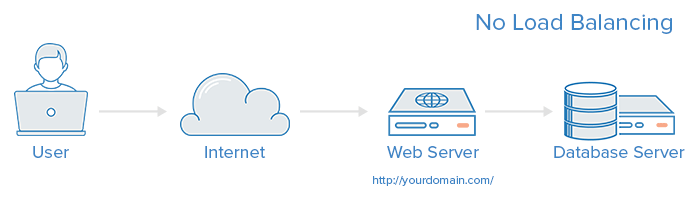

Load balancing is a key component of highly-available infrastructures commonly used to improve the performance and reliability of web sites, applications, databases and other services by distributing the workload across multiple servers.A web infrastructure with no load balancing might look something like the following:

In this example, the user connects directly to the web server, at yourdomain.com. If this single web server goes down, the user will no longer be able to access the website. In addition, if many users try to access the server simultaneously and it is unable to handle the load, they may experience slow load times or may be unable to connect at all.

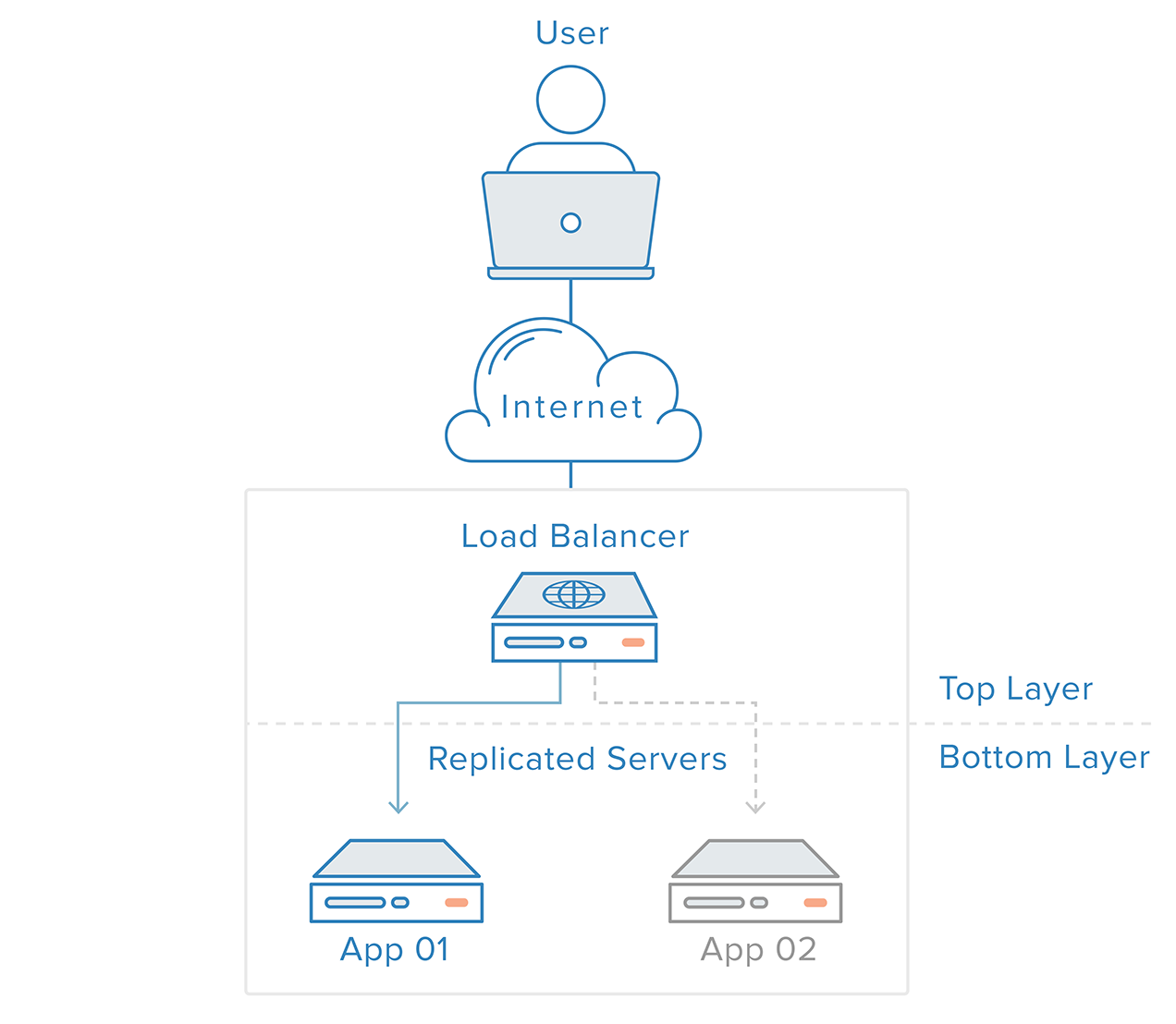

This single point of failure can be mitigated by introducing a load balancer and at least one additional web server on the backend. Typically, all of the backend servers will supply identical content so that users receive consistent content regardless of which server responds.

What kind of traffic can load balancers handle?

Load balancer administrators create forwarding rules for four main types of traffic:- HTTP — Standard HTTP balancing directs requests based on standard HTTP mechanisms. The Load Balancer sets the

X-Forwarded-For,X-Forwarded-Proto, andX-Forwarded-Portheaders to give the backends information about the original request. - HTTPS — HTTPS balancing functions the same as HTTP balancing, with the addition of encryption. Encryption is handled in one of two ways: either with SSL passthrough which maintains encryption all the way to the backend or with SSL termination which places the decryption burden on the load balancer but sends the traffic unencrypted to the back end.

- TCP — For applications that do not use HTTP or HTTPS, TCP traffic can also be balanced. For example, traffic to a database cluster could be spread across all of the servers.

- UDP — More recently, some load balancers have added support for load balancing core internet protocols like DNS and syslogd that use UDP.

How does the load balancer choose the backend server?

Load balancers choose which server to forward a request to based on a combination of two factors. They will first ensure that any server they can choose is actually responding appropriately to requests and then use a pre-configured rule to select from among that healthy pool.Health Checks

Load balancers should only forward traffic to "healthy" backend servers. To monitor the health of a backend server, health checks regularly attempt to connect to backend servers using the protocol and port defined by the forwarding rules to ensure that servers are listening. If a server fails a health check, and therefore is unable to serve requests, it is automatically removed from the pool, and traffic will not be forwarded to it until it responds to the health checks again.Load Balancing Algorithms

The load balancing algorithm that is used determines which of the healthy servers on the backend will be selected. A few of the commonly used algorithms are:Round Robin — Round Robin means servers will be selected sequentially. The load balancer will select the first server on its list for the first request, then move down the list in order, starting over at the top when it reaches the end.

Least Connections — Least Connections means the load balancer will select the server with the least connections and is recommended when traffic results in longer sessions.

Source — With the Source algorithm, the load balancer will select which server to use based on a hash of the source IP of the request, such as the visitor's IP address. This method ensures that a particular user will consistently connect to the same server.

The algorithms available to administrators vary depending on the specific load balancing technology in use.

How do load balancers handle state?

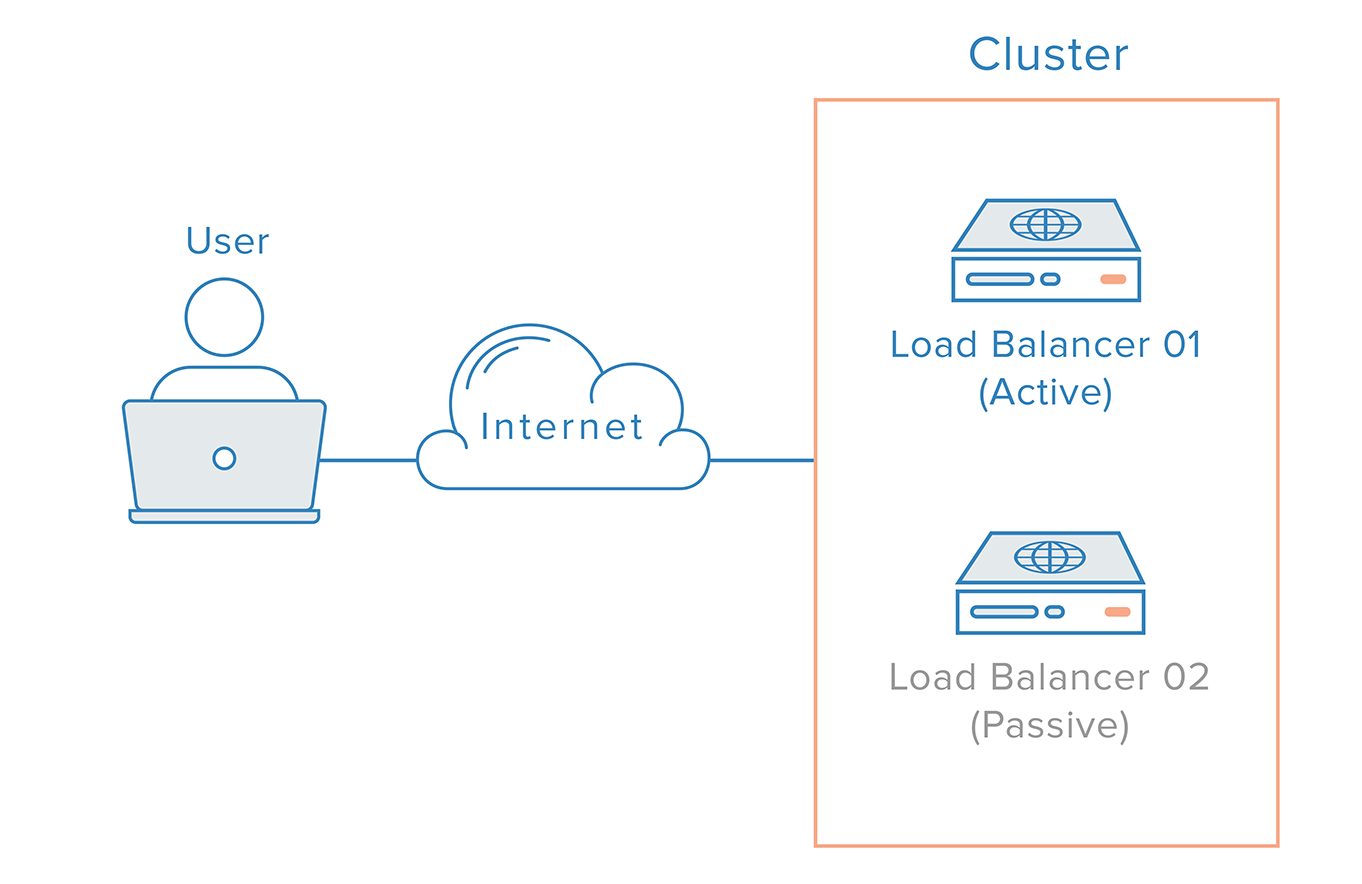

Some applications require that a user continues to connect to the same backend server. A Source algorithm creates an affinity based on client IP information. Another way to achieve this at the web application level is through sticky sessions, where the load balancer sets a cookie and all of the requests from that session are directed to the same physical server.Redundant Load Balancers

To remove the load balancer as a single point of failure, a second load balancer can be connected to the first to form a cluster, where each one monitors the others’ health. Each one is equally capable of failure detection and recovery.

This is how a highly available infrastructure using Floating IPs might look:

Conclusion

In this article, we've given an overview of load balancer concepts and how they work in general. To learn more about specific load balancing technologies, you might like to look at:DigitalOcean's Load Balancing Service

- How To Create Your First DigitalOcean Load Balancer

- How To Configure SSL Passthrough on DigitalOcean Load Balancers

- How To Configure SSL Termination on DigitalOcean Load Balancers

- How To Balance TCP Traffic with DigitalOcean Load Balancers

HAProxy

- An Introduction to HAProxy and Load Balancing Concepts

- How To Set Up Highly Available HAProxy Servers with Keepalived and Floating IPs on Ubuntu 14.04

- Load Balancing WordPress with HAProxy

Comments

Post a Comment

https://gengwg.blogspot.com/